An Interview With Christian Van Horn

Christian Van Horn (Dario Acosta)

Twelve years on from his debut at the Met Opera, bass-baritone Christian Van Horn has made a name for himself as opera’s definitive Devil. Last September, for his fourth performance in Live in HD, he scored another success as not one but all four Villains in Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann. He kindly spoke to me about his podcast, his upcoming album (shh!), and winning his first Girl of the Golden Met Award. Read on!

Christian did not grow up listening to classical music, but to Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell. Unusually for a world-renowned opera singer, what first gave him the singing bug was not his first opera, but Elvis, which his father introduced him to. His path began in the church choir and later high school musicals (he starred in shows such as Leader of the Pack and Cinderella), and eventually led him to study voice at SUNY in Stony Brook. When his voice teacher, Richard Cross, left to teach at the Yale School of Music, Christian followed him to the school, where Cross told him ‘Well, we don’t have any room for you, but come up and audition anyway.’ Christian’s audition conjured up a spot — the Devil works in strange ways. He was a “small fish in a small pond”; at the time, the program had only fifteen singers, and as a result, there was no place for the young bass-baritone to hide in the background. Devil take the hindmost.

Slowly but surely thriving under Cross, Christian saw his first opera in 1998: Falstaff at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino in Florence, Italy, starring Jean-Philippe Lafont. Christian “fell in love with the live performance, the theater, the space between the audience and the proscenium where the magic happened.” This stunning experience foreshadowed his debut at the Met Opera, which came in the role of Pistola, one of the titular character’s henchmen in Falstaff.

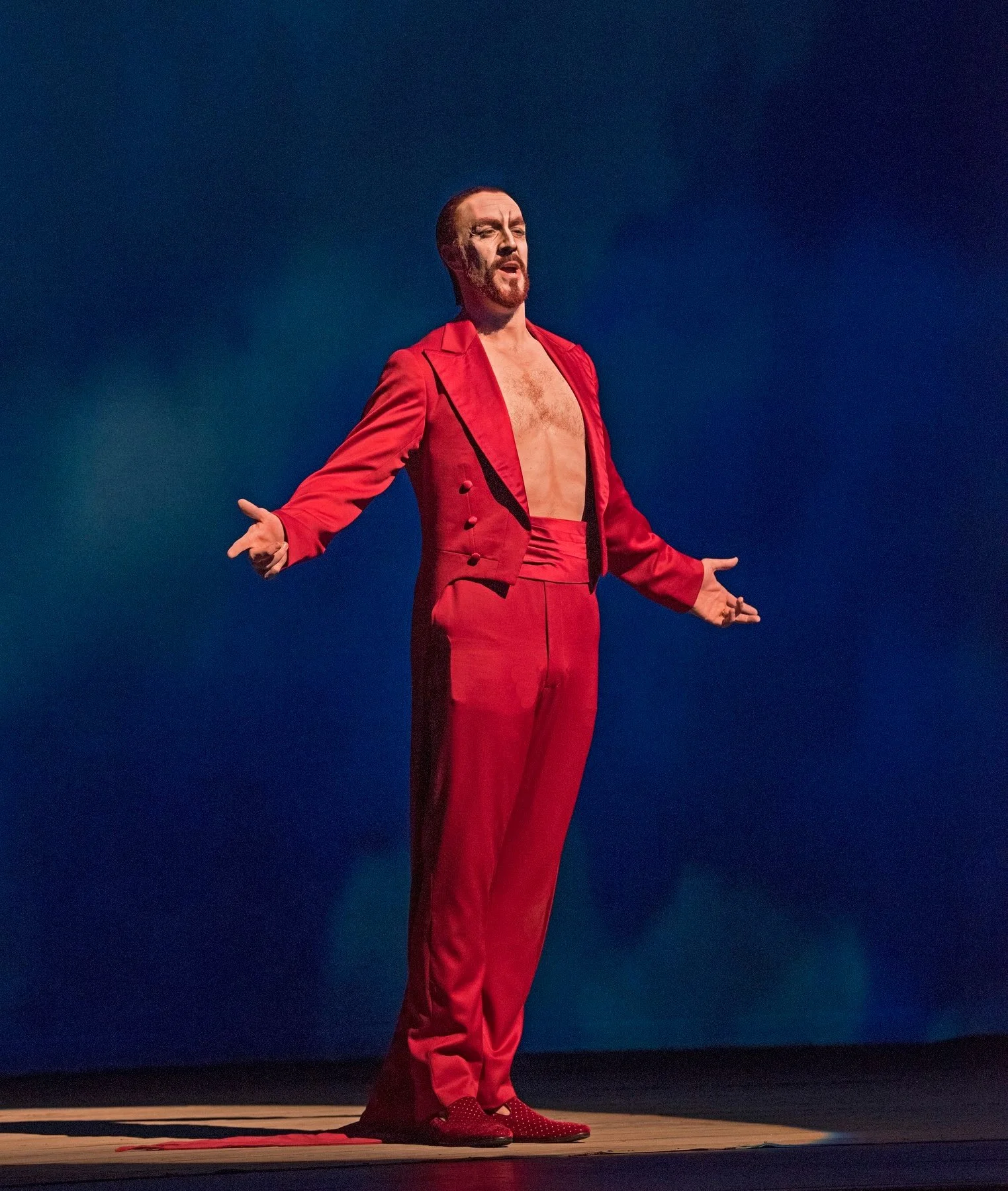

Christian in Mefistofele (Karen Almond/Met Opera)

As aforementioned, he has a signature character as opposed to a signature role: the Devil, which he has played to acclaim in Boito’s Mefistofele, Gounod’s Faust, and Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress. Even Lindorf, the first of the Four Villains in Hoffmann and arguably behind all of the other Three, Christian describes as a “devil in disguise.” He explains his approach to singing devils, and indeed villains in general: “The trick is to make any evil character sympathetic. When I’m singing the Devil, Méphistophélès or Mephisto, even Don Giovanni, I want you to root for them, even when they’re the bad guy.” It’s hard not to root for Christian onstage, even with Satan’s red horns or Lindorf’s demoniacal laugh.

However, by no means does he exclusively sing villains. The two roles currently most “close to [his] heart” are King Philippe in Don Carlos and the title character of Massenet’s Don Quichotte. The former is an antagonist, to be sure, but he’s Mr. Rogers compared to Don Carlos’s true villain, the Grand Inquisitor. One needs only minimal familiarity with literature to know that Don Quichotte is misguided, gullible, and half-mad, but not villainous. “My performance of these characters stems from my own reality, so whether it’s dealing with death or having your heart broken or going through trials and tribulations, that’s giving me the opportunity to be a real artist.”

Then there are the one-dimensional roles, like Escamillo in Carmen, who swaggers shallowly through his sea of fans. This sort of character is especially tricky to keep from making into a “cartoon”. The key, according to Christian, “is to make sure the relationships are true.” In Escamillo’s case, “fight[ing] that one-dimensional character” translates into an effort to ensure that “the connection with Carmen is real.” So often, roles — and people — are defined by their relationships with the people around them, and Carmen is the most important person in Escamillo’s stage time.

Christian with Pretty Yende in Les Contes d’Hoffmann (Ken Howard/Met Opera)

Last month, Christian won Best Bass-baritone/Bass at the 2025 Girl of the Golden Met Awards for his formidable Four Villains in Les Contes d’Hoffmann. “It’s pretty rare that there’s a category for basses, bass-baritones, and baritones” in any opera awards contest, noted Christian, and this year was the first that there was a separate category for bass-baritones and basses, rather than putting them with the baritones. “I was thrilled, absolutely thrilled to just be considered,” he said, especially alongside his fellow nominees Michael Volle, Rene Pape, and Sir Bryn Terfel. “These guys were my heroes, and so to even be considered along with them is great.” Humbly, he acknowledged: “I take an unfair advantage because that older generation didn’t mess around with social media and I do!” However, at the end of the day, it was the will of the people. “It meant the world.”

Even as one of the, if not the, world’s leading bass-baritones, Christian has never recorded a solo album. Asked why, he explains that “music recording contracts are few and far between, simply because they cost a fortune to do and they don’t make money. People don’t buy albums anymore; people stream... It could cost you X dollars to record 15 tracks, but really the majority of people are only going to listen to three or four of them. And that’s unfortunate, but it’s reality. It’s a losing money game.” I heard that sigh of disappointment, readers… but wait! Having thoroughly detailed the reasons not to make an album, Christian revealed that he is, in fact, making “a solo recording, about 12 or 15 arias” after all, because “I believe in getting my shot.” We’ll have to wait for more details, but “there are plans for that in the works. It’s happening next year.” You heard it here first!

Christian at the microphone (Chris Gonz)

Speaking of recording, let me take you back to 2020. As the loneliness of lockdown was driving people around the world nearly out of their minds, Christian started the CVH Podcast. “We were all out of business, nobody was working, and I wanted to talk to the audience. I needed to connect with people again, and I needed to use my voice.” He tells stories about his career and speaks his unfiltered thoughts about topics as varied as motivation, baseball, and Skittles for breakfast. “Unfiltered” is not an exaggeration; seeking maximum authenticity, Christian never rerecords or edits the episodes, not even cutting out coughs. “I want the audience to feel like they’re sitting with me, and that I’m a trusted friend, and I tell them the truth, I don’t sugarcoat things, I don’t make things up.”

It didn’t take long before other opera singers started joining him on the podcast, including his close friends Quinn Kelsey (four-time guest) and Étienne Dupuis (five times). Christian’s wishlist of guests is just “people who are comfortable enough with me to be completely and wholly honest,” instead of giving “the People Magazine answer… People believe that the singer life is charmed and extravagant and glamorous, and really a lot of it is not that.” Long after the end of lockdown, the CVH Podcast has endured. “Here we are, almost 5 years later, 280 episodes later, it’s turned out to be this incredible tool of connection between me and the audience.” It’s the gift that keeps on giving — like Christian to the opera world.